How to Draw a Perfect Circle Terrance Hayes Analysis

Voluntary Imprisonment

The staid sonnet is i of the oldest forms of poetry. Terrance Hayes transforms information technology.

This essay is adapted from Don't Read Poesy: A Volume Virtually How to Read Poems, out now from Bones Books.

Verse is for everyone, but it can't exist the same affair, or do the same affair, for anybody. Poems can console or upset, soothe or bamboozle, set the table for a fancy dinner or kick the table over and demand that we showtime again. It depends how you read them, and it depends what verse form. Every bit America'due south youth poet laureate, Kara Jackson, has recently written, "the most dangerous thing about how we treat verse is how we allow only old white men have it." What'southward truthful for verse in full general is no less truthful for particular kinds of poems, techniques, and forms. And if that's truthful for modern poems and for poems in new forms (say, those that resemble text messages), it's no less true for poems in very traditional forms—the sonnet almost of all.

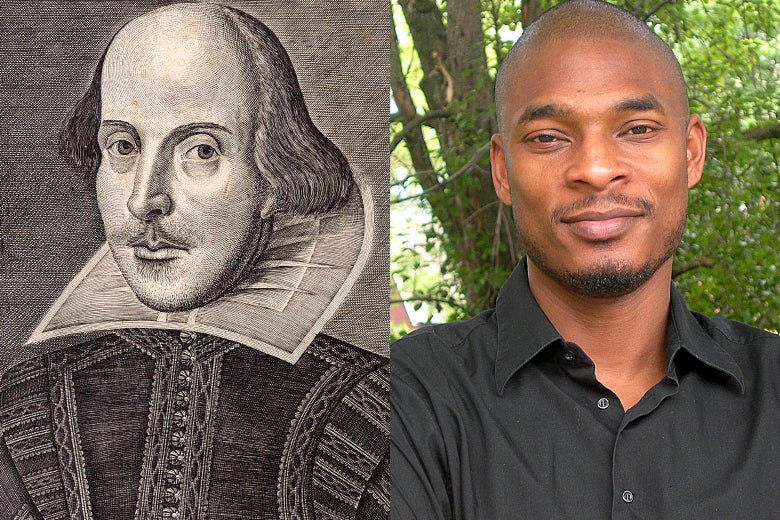

The sonnet isn't the oldest course in English, only information technology may be the most recognizable, the one we encounter beginning in middle and loftier schools, the one Shakespeare used 154 times. To write a sonnet at all, these days—let alone a book of sonnets—is to speak to, or talk back to, the past. If yous know what a sonnet is—14 lines, usually, 10 syllables each; rhymed, usually; divided into 2 parts, or else four, with a couplet—yous probably also know that they're centuries old. Merely yous may not know how thoroughly modern poets take reinvented the grade. And no living American poet has done so more assiduously than Terrance Hayes, whose 2018 volume American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin amounts to a primer on how to reshape an onetime form.

Hayes has taken up—or taken down—the sonnet sporadically throughout his career, near famously with a bout de strength chosen "Sonnet" in 2002's Hip Logic; the poem comprises fourteen repetitions of the same line, "We cut the watermelon into smiles." Hayes's fourteen iterations play on racist stereotypes that acquaintance rural blackness Americans with watermelon and fixed grins, and on the assumption that all sonnets say or hateful the same affair. He as well points back to the black author Paul Laurence Dunbar's famous stanzaic lyric of 1896: "We wear the mask that grins and lies."

But American Sonnets is something bigger than that. Usually in a collection of sonnets each will have a different championship, or (as in Shakespeare) no title at all. Instead, each poem here has, over and over, the same title: "American Sonnet for My Past and Future Assassin." Hayes' 14-line projects react to the poet'southward own frustration with his fame (which eats upwards his fourth dimension with worthy obligations, isolates him, and cannot give him peace), too as reacting fiercely to America under Trump. Hayes' new sonnets also replace conventional rhyme schemes with much denser sonic arrangements, often untethered to line ends. One of them insults a critic "who cannot distinguish a blackbird from a raven": "You don't know how/ To describe your own face. In the mirror you coo/ Gibberish where the shape of your oral fissure escapes you lot."

Hayes's sonnets know how sonnets are supposed to audio, how older sonnets do sound, with the rhymes at the cease; he's stuffing his own sonnets full of midline rhymes instead, and so omitting rhymes where a reader might expect them, while keeping the expectations in mind. (Hayes credits the California poet Wanda Coleman with the invention of the "American Sonnet," which need not rhyme.) Another sonnet lets loose on politicians whose words are all lies or meaningless sounds: "Junk country, stump speech communication. The umpteenth boast/ Stumps our toe. The umpteenth falsehood stumps/ Our elbows & eyeballs, our olfactory organ & No's, woes & whoas." The cascade of open vowels, the near show-offy feel in these repetitions (Hayes uses the discussion umpteenth 8 times in xiv lines) suggest a fed-up citizen, and too a writer whose expertise with words adds to his moral potency: Somebody who can write similar that knows, if anybody knows, what words can practise.

Simply Hayes isn't just conducting sonic experiments. Nor is he just representing his acrimony at Trump and Trumpism. (A book of sonnets that did nil else would start to repeat itself fast.) He'due south too inverting traditional stories nigh the power and the tragedy in the making of lyric poems. In the most famous Western myth on that subject field, the non-quite-divine musician Orpheus sang so beautifully that he persuaded the god of the underworld to allow him bring his late married woman dorsum from the expressionless, and so lost her when he turned effectually to look at her on her mode back to life. That myth proposes that lyric poesy is at base erotic, well-nigh attachment; that information technology is first and final about grief or lack or loss; that it feels magical that it can contradict facts (for example, the fact that death is forever); and, maybe, that it is really nearly itself—true poets might not so much sing about their dearest as beloved in lodge to sing. The start sonnet in American Sonnets for My Past and Future Assassin concludes in an anecdote about Orpheus:

Orpheus was alone when he invented writing.

His manic cartoon became a kind of writing when he sent

His beloved a sketch of an center with an X struck through it.

He meant I am blind without you lot. She idea he meant

I never want to run across yous again. It is possible he meant that also.

Does he want his honey back? Or does he want to write poems? That 10, that crossed-out eye, that visible sign of blindness, that letter that could exist a number or an algebraic variable, reflects a severe division, a poet who wants mutually sectional things. A after sonnet decides that "Eurydice is actually the poet, not Orpheus. Her muse/ Has his dorsum to her with his ear bent to his own heart."

Literary history—and Western history—in this view is a series of misattributions, where readers and listeners and writers credit the captor, the pursuer, the abductor, with what the captive has fabricated upwardly. Resemblances to the history of popular music, where white people take credit for black forms, are surely not coincidental. Nor is it a coincidence that the sonnet—a form compared (by William Wordsworth) to nuns' cells, to a voluntary imprisonment—appeals to a poet whose female parent was a prison house guard, whose cousin has been incarcerated, who has written over and over, brilliantly, about the carceral country. (Hayes has also recently published a fine book-length written report of the poet Etheridge Knight, whose get-go and best-known book is Poems from Prison .)

Wordsworth made lite of the kind of confinement that sonnets and their stanzas correspond: "In truth, the prison house unto which we doom/ Ourselves, no prison is; and hence for me… Within the Sonnet's scanty plot of ground." Hayes seeks culling models for the sonnet and its pleasurable, melancholy solitude: It is non then much a jail cell as an "envelope of wireless chatter," a grave, an "orphan's house," "the sweat & rancor of a Fish & Chicken Shack," "the broken telephone berth I passed in the Village/ Beside a pool of what could have been crushed tomatoes." Hayes'south sonnets may experience cramped or uncomfortable, only they can attend the states; we tin leave at any time.

Is poetic technique a means of liberation? Or does adopting inherited techniques amount to surrender, and to solitude? In some sense the answer is always "both." Another 1 of Hayes' American Sonnets takes the ideas of body equally prison and poetic form every bit both liberation and confinement further however. The poet, fed upwardly with himself and with his club, tells himself, or part of himself:

I lock you lot in an American sonnet that is office prison,

Part panic closet, a little room in a house set aflame.…

I lock your persona in a dream-inducing sleeper hold.…

I make you a box of darkness with a bird in its centre.

Lyric poetry—the poet imagines—works past finding words for someone's passions, which could also be your own: information technology tin can get yous out of your one state of affairs, your one body, your one life, though it will non literally free you lot from a literal jail. It may have upwards many aspirations to liberty, from the traditions of prison house writing to the tradition of existential rebellion confronting everything that exists. It needs, in that example, something to insubordinate against. And for Hayes—as for poets before him—the sonnet serves uncommonly well.

Slate has relationships with diverse online retailers. If y'all buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate committee. Nosotros update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

Source: https://slate.com/culture/2019/05/terrance-hayes-sonnet-poetry-stephanie-burt.html

0 Response to "How to Draw a Perfect Circle Terrance Hayes Analysis"

Post a Comment